Sustainable Graphic Design

Recently I’ve been thinking a lot about the impact graphic design has on the world, and working out how I could make my practice as sustainable as possible. It’s a journey I started a while ago, but it isn’t something I’ve always got right, and I’m certainly guilty of having been seduced by less sustainable papers and print processes. But I’m intent on being a better designer going forwards. So I thought I’d collect and share what I’ve learnt about sustainable graphic design here – for my clients and for any other designers thinking about the same topic. (As I design primarily for print, I’ll focus on that, but will touch on digital design as well.)

THE SITUATION

We’re in the throes of a climate crisis. A unique moment in humanity’s history, and the defining challenge of our generation. Thanks to increased greenhouse gases in the atmosphere – due to the burning of fossil fuels over generations, as well as deforestation and intensive food production – global average temperatures worldwide are climbing. This is leading to rising sea levels; stronger, more frequent storms and floods; as well as more frequent and extreme heatwaves, wildfires, droughts and famine. Biodiversity is decreasing at an alarming rate because of the changing climate and habitat loss. Add to that the increased pollution of our land, sea and air, and things look really bleak.

But all is not lost – not yet. The hope is that if we all do our bit, from governments to corporations to individuals – in effect a species-wide effort – we can drastically reduce our use of fossil fuels, limit the temperature rise, and avert the worst effects of the crisis. But we have to act now, before we reach certain tipping points: natural thresholds beyond which climate change suddenly and catastrophically accelerates, and from which there’s no way back.

OUR PARTICULAR PROBLEM

Graphic Design is a generative process – we make stuff. Loads of stuff. Printed stuff like books, newspapers, magazines, leaflets, posters, product packaging, banners and stationery; or digital stuff like websites and apps. The printed stuff uses energy and materials in its production and delivery, and will more than likely end up in landfill; the digital stuff uses energy in its production, hosting and consumption. So it’s imperative that we do the best we can to produce that stuff with the lowest possible impact.

THINGS WE CAN DO

First and foremost, we can choose the clients we design for. Obviously not working with companies whose products cause significant harm to the planet or society is a good start. Avoiding fossil fuel companies, arms manufacturers, and tobacco companies perhaps goes without saying. On my personal list of companies to avoid, I’ve added alcoholic beverage companies, major plastic polluters (Coca-Cola, Pepsico, Nestlé, Unilever and Mondeléz), fast fashion and fast food companies, and airlines. (Ethical Consumer has a useful and detailed scoring system for lots of businesses that work directly with the public – you just need to subscribe to see their scores.) I’ve always worked with organisations I respect and admire – from the National Trust to the Ministry of Stories and London Cycling Campaign – but now I’m making that an explicit part of my studio’s remit: working with organisations who are actively doing good things for the planet or society – ideally both.

Secondly, we can look at our own studios’ carbon footprints. Commuting to work by foot, bike or public transport; using renewable energy; reusing and recycling as much as possible; making IT equipment last as long as possible; hosting websites on green servers – these are all good things. But by far the most impactful thing you can do is make sure your workplace pension scheme invests your money ethically – check out Make My Money Matter for more on that.

Thirdly, we can make sure the stuff we produce is done so as sustainably as possible. For printed stuff, that means looking at the papers we use, the formats of the things we make, the printers we work with, the printing and binding processes we specify, the shipping distance of the finished pieces, and their reusability and recyclability. (The more copies you’re producing of something, the more important each of those decisions becomes.) For digital stuff, it means doing as much as possible to keep the energy use of any website or app as minimal as possible.

I’m going to look into each of those aspects in more detail further below.

FINDING INFORMATION

When trying to work out the best way to do things, I’ve been hunting around for some authoritative sources of information. (Searching for ‘sustainable graphic design’, ‘green graphic design’ and ‘environmentally friendly graphic design’ pulls up a mixed bag of stuff.)

There are general environmental organisations, like Greenpeace, Friends of the Earth and WWF. Of those, the WWF has a really useful Business Resources Hub, with information about how to reduce your business’s environmental impact. From there you can download their Paper, Timber and Print Purchasing Policy – which is a great template for best practice when you’re producing communication materials.

Re-nourish, a US nonprofit organisation which “provides online tools and advocates for awareness and action for life-centered systems thinking in the visual communication design community”, also has useful guides on sustainable printing and paper choices. It also has a set of standards to aim for when creating a printed or digital project, as well as case studies of projects which have met those standards. They also have a paper and printing worksheet, which is a useful reference guide for best practice.

I’ve signed up to Design Declares: “a growing group of designers, design studios, agencies and institutions here to declare a climate and ecological emergency. As part of the global declaration movement, we commit to harnessing the tools of our industry to reimagine, rebuild and heal our world.” Sign up and you can access the Design Declares Toolkit, a set of web pages hosted on the Notion platform, providing really helpful resources, case studies and articles about sustainable design for communication, digital, industrial and service designers.

One of the areas where I don’t feel like there’s a concrete answer is the question of print vs. digital, and which does the least amount of environmental harm. Is it better to print a report, or to host it online? Both use significant amounts of energy – print for production and transportation, digital for hosting and use (while you’re reading this post, a Cloudflare server in Amsterdam is humming along, running on electricity, and needing a vast amount of water to stay cool; and the device you’re reading it on is also using electricity.) Given how hard it is to get an accurate sense of their respective environmental costs, it seems that for now we should focus on their functionality. Printed publications can draw and hold attention in a way something digital might not. But digital information is quicker to produce and distribute (generally) and much easier to update. But print is often seen as more trustworthy – partly because it feels like more effort and thought will have gone into its creation, but also because it can’t be changed remotely.

Worryingly, it seems that our professional design organisations (D&AD, AIGA, AGI, Chartered Society of Designers) don’t, at the time of writing, have much to say about sustainability. The exception is the Design Council, which hosts an annual Design for Planet Festival (with recordings available of talks from previous years), and has regular Design for Planet Meet Ups in person and online.

PAPERS

Making up the bulk of most printed publications, choosing a sustainable paper is essential. Fortunately, when sourced properly, paper is a sustainable material – take a look at Two Sides for more on the subject.

Re-nourish advises choosing a non-wood paper if possible (made with agricultural fibres – like wheat straw or hemp,) or wood-based paper made from 100% Recycled Post Consumer Waste (PCW) if not – that’s made entirely from material that would otherwise have gone to landfill.

It should also be unbleached if possible, or processed chlorine free (PCF) – this means the recycled fibres have been bleached using chlorine-free compounds. (You can’t guarantee that the virgin fibres weren’t originally bleached with chlorine, but PCF means it hasn’t been used during the recycling process.) With non-recycled papers, you can choose totally chlorine free (TCF), which use less harmful hydrogen peroxide for bleaching instead.

If you can’t use a non-wood paper, or 100% Recycled PCW paper, your next best option is to specify papers that are certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). They provide a globally recognised certification scheme which helps ensure “socially, economically, and environmentally responsible management of the world’s forests.” More specifically, their responsibly managed forests “provide us with clean air, and clean water – by restricting hazardous chemicals, and following FSC harvesting and forestry practices that minimise degradation and erosion. They ensure a diversity of animals, trees and other plants; as well as safe working conditions. They provide better jobs for the local community and respect the rights of local people.”

They have three types of certification:

FSC Recycled

All the forest-based materials in products or packaging bearing this label have been verified as being 100% recycled (either post-consumer or pre-consumer reclaimed materials).

FSC 100%

All forest-based materials in products or packaging bearing the FSC 100% label must be sourced from FSC-certified forests.

FSC Mix

All forest-based materials in products or packaging bearing the FSC Mix label must either be from FSC-certified forests, verified as recycled or classed as controlled wood. Controlled wood is not from FSC-certified forests but it mitigates the risk of the material originating from unacceptable sources.

Papers with Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC) certification are also fine to use, with high standards for forest management and the chain of custody. This page from the PEFC site explains their various certifications. Some papers (and forests) have both FSC and PEFC certification.

The WWF print procurement policy advises 100% Recycled Post Consumer Waste papers, and if not, then FSC Recycled, FSC 100%, or FSC Mix, in that order of preference, and recommends using uncoated stocks. The more locally the stock has been manufactured, the better.

Park Communications has a useful Paper Finder Tool you can download, which details a wide variety of recycled stocks from the main UK paper suppliers: Antalis, Denmaur, Fedrigoni, Fenner, and G·F Smith (who are another certified B Corp). You could also check out Paperback, who specialise in recycled stocks. Have a look at A Better Source for a helpful list of recycled and wood-free stocks. Or just chat with your printer or paper supplier – they will be more than happy to help you.

Choosing a lighter weight stock is also a good idea if possible – if you’re worried about the finished piece feeling too insubstantial, you could look at using a bulkier stock, which is thicker (measured in microns, 1000th of a mm) than a standard stock of the same weight (measured in gsm, or grams per square metre).

FORMATS

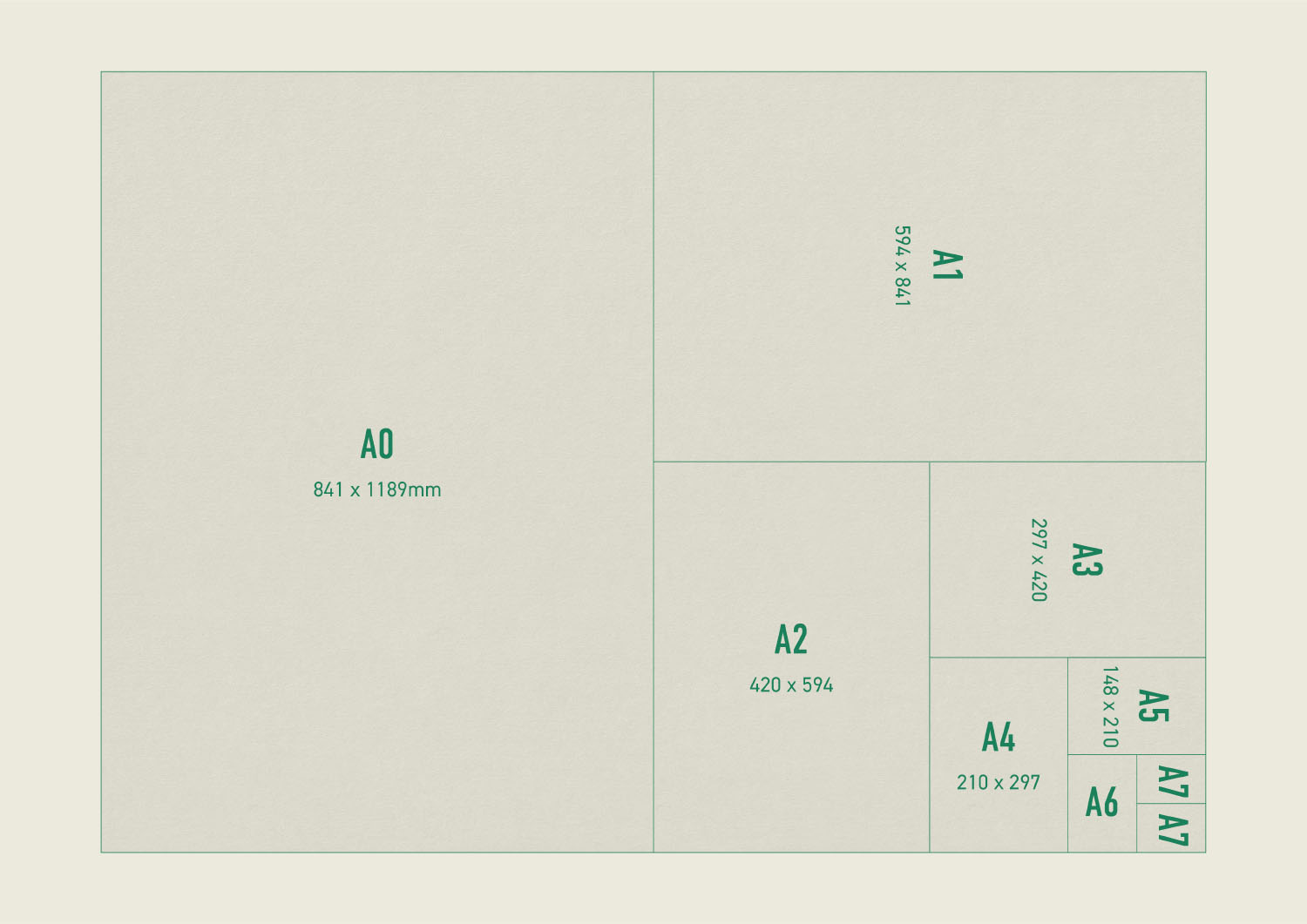

When you’re printing a job, the pages are laid out onto larger sheets, and then cropped down to size. The sheet size depends on the stock you’ve chosen, and the size of press you’re printing on.

In the UK we use standard A sizes for many common publications, and these can often be the most economical to print, going on to SRA size sheets, which match to the A sizes, with additional space for crop and bleed, and for the press to grip the paper. There are also B size sheets, with B1 sheets being a common size provided by paper merchants – though oddly the B1 sheet size varies from manufacturer to manufacturer. Justin Hobson from Fenner paper has written this informative blog post all about it.

By chatting to your paper supplier and printer, you can make sure that there is as little waste as possible.

PRINTERS

If you’re designing printed work, then you want to make sure that the printer you work with is working as sustainably as possible. There are various schemes and accreditations that are worth looking out for.

First up your printer should be ISO 14001 certified – that’s a globally recognised Environmental Management certification from the International Organisation for Standardisation. “It provides a framework for organisations to design, implement, and continually improve their environmental performance. By adhering to this standard, organisations can ensure they are taking proactive measures to minimise their environmental footprint, comply with relevant legal requirements, and achieve their environmental objectives.” If you’re printing within the EU, then the EU Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS) is similar, if slightly more strict. Some UK printers still work to the EMAS standards.

Your printer should also have FSC Chain of Custody certification from the Forest Stewardship Council. As I mentioned above, the FSC is an international NGO whose mission “is to promote environmentally appropriate, socially beneficial, and economically viable management of the world’s forests”. The chain of custody certification is how the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) “verifies that forest-based materials produced according to our rigorous standards are credibly used along the product’s path from the forest to becoming finished goods. The FSC label on a finished product signals that the materials used during production have met the chain of custody requirements at every step in the supply chain, from sourcing to distribution.” Which basically means that if your printer says they’ve used FSC certified paper, you can be sure that they have. This FSC in Print document explains it all very clearly.

You could also look for printers which have certified B Corporation status: “B Corp Certification is a designation that a business is meeting high standards of verified performance, accountability, and transparency on factors from employee benefits and charitable giving to supply chain practices and input materials.”

There’s also the Planet Mark: “a recognised symbol of sustainability progress. It demonstrates a business’ commitment to measuring and reducing their carbon emissions, ultimately contributing to their environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria.”

And you could look for printers who display the Carbon Balanced mark, a scheme delivered through the World Land Trust, for printers using Carbon Balanced Paper: “Choosing Carbon Balanced Print and Paper helps fund World Land Trust’s ecosystem protection and restoration projects in Vietnam, Mexico, Ecuador and Guatemala. Contributions to the Carbon Balanced programme are used to protect land from deforestation and degradation, preventing the release of CO2 into the atmosphere while preserving invaluable ecosystems.”

It’s worth noting though that the whole topic of carbon offsetting is problematic when it comes to actual carbon reduction, as you can see from this Guardian article.

Your printer should be able to advise you on the best way to reduce the environmental impact of anything you’re designing. You also want a printer that is near to you and your client, so that you can check work on press, and so that the transportation distance for the finished print is as short as possible (assuming that the print is being delivered to the client).

Here are a few good UK-based printers I’ve worked with who are close to London, ISO 14001 and FSC certified, and focused on sustainability:

• Park Communications (east London – Park also have a useful free downloadable Sustainable Print Design handbook, though with a slightly more lenient mindset than organisations like Re-nourish and WWF.)

• Rapidity (central London)

• Impress (Walton-on-Thames, for litho printing they use vegetable-based inks, and run on renewable energy)

• Generation Press (Brighton, for litho printing they use vegetable-based inks, run on renewable energy, and they’re also a B Corp)

• Pureprint (East Sussex)

PRINTING AND BINDING

Once you’ve sorted out the format of your project, the stock you’re printing onto, and the printer you’re working with, you should also think about the printing processes you’re using, and the type of binding you’re specifying.

Choosing between litho and digital printing is generally a choice that’s determined by the size of your print run, both from financial and environmental standpoints. Digital printing seems to be slightly more environmentally friendly (low waste, minimal solvent use, water-based inks, no printing plates), but economies of scale mean things balance out on larger print runs. Digital print can be recycled, but there do seem to be some concerns about how easy the de-inking process is. I’ve mainly printed work on HP Indigo presses, and this is what they have to say about de-inking in their Sustainable Impact Overview: “Deinking of paper: HP presses are compatible with over 1,900 certified media with environmental credentials, and prints can be recycled into useful fiber-based materials.”

Reducing the ink coverage on each page is beneficial, in consumption of materials and energy during production, and also when it comes to recycling.

For litho work, working with a printer who uses vegetable-based inks is a great start, and Re-nourish also recommends having no inks with heavy metal additives – found in most fluoros and metallic inks, and no “varnishes, laminates and UV coatings (aqueous coatings and engravings are acceptable)”. The WWF print purchasing policy emphasises that it’s good to avoid even biodegradable lamination, “as the adhesives used to apply them can cause recycling problems”.

Foil blocking with hot stamping foil isn’t much of a hindrance when it comes to recycling, but does involve the production of metal dies, and potentially additional transportation if this part of the process has to be outsourced to a separate printer. This page from foil supplier Foilco covers the main environmental questions.

Blind embossing or debossing still involves the production of a metal plate, but does avoid the use of an extra material.

When it comes to binding, less is definitely more – the fewer materials involved, the less energy used, and the easier the piece will be to recycle. Saddle stitching (stapling) uses steel stitches which are magnetic, so can be easily removed during recycling. Metal wiro binding can also be removed and recycled easily. Thread-sewn and singer-sewn bindings are also glue-free options, though quite expensive, and may require the print being transported to a separate company. If you have to use a glue binding, PUR binding is stronger and uses around 70% less adhesive than standard perfect binding.

Making sure that you’re not printing more copies than are really necessary is also hugely important. It can be tempting to overprint ‘just in case’, but that can lead to boxes of unused leaflets, brochures or books, which will sit in a storeroom for years before being recycled, or often, binned. Realistic assumptions about audience numbers helps here. Similarly, it’s really important to keep contact / mailing lists up to date, so that things aren’t being sent to the wrong address, where again, things will end up in the bin.

ENCOURAGING RECYCLING

Making sure your audience knows that you’ve used sustainably sourced materials makes good sense. Your FSC certified printer will be able to supply you with a suitable FSC logo (as shown in the previous section) which shows how much recycled content has been used in your paper.

More importantly though, you should encourage recycling of your finished piece (or reuse if possible). You can get recycling logos like the one above from Wrap, and the dedicated site recyclenow.com has a useful page explaining the many other recycling symbols. Alternatively you can add your own text asking your audience to recycle the piece – if it’s made of more than one material, make it clear how to recycle each part.

COST

Many of the resources around sustainable graphic design are a little shy of discussing the financial costs involved. The Park Sustainable Print Design handbook however notes that recycled papers are at least 30% more expensive than virgin fibre stocks. So sustainable print design can cost more than the standard equivalent. But the more clients and designers insist on sustainable options, the faster that price difference will evaporate, and before long the sustainable choice will be the more cost effective choice. In the meantime, creative thinking around formats, printing processes and binding can be used to offset higher material costs.

And perhaps we just need to flip the way we think of the two options anyway? If you have a choice between a standard, sustainable version, and a cheaper unsustainable planet-harming version, the choice seems quite simple.

DIGITAL DESIGN

When it comes to digital projects, particularly web design, there are a few great places to look for information. Sustainable Web Design is a fantastic resource, which offers “an approach to designing web services that puts people and planet first”. It has a set of really clear and specific Web Sustainability Guidelines which are grouped by subject area (UX Design, Web Development, Hosting & Infrastructure, Business & Product Strategy). You could also take a look at Re-nourish’s design strategies for UI/UX Design, and at the resources page at lowwwcarbon.com.

The main aim is to create sites which use as little energy as possible, and which work as well as possible, so that people can find what they’re looking for quickly and easily. So for web design, that would mean: efficient code, well-structured navigation, only using images when necessary and making sure their size is optimised, allowing lazy loading, including alternative text, and hosting sites on servers powered by renewable energy (rather than through carbon offsetting, which as I mentioned earlier, is a complicated area).

You can get an estimate of a webpage’s carbon footprint using websitecarbon.com (though as Nicolas Paries from Hey Low studio points out, measuring the carbon emissions of digital products is an inexact science).

FINAL THOUGHTS

If you think about the meanings of the word sustainable – ‘able to be continued at the current rate or level; able to be upheld or defended’, and then the opposite, unsustainable – ‘not able to be continued at the current rate or level; not able to be upheld or defended’, then it becomes startlingly clear that sustainable design is the only way forward. Sustainability is simply essential.

Hopefully this post has helped explain the options for sustainable graphic design. Please do share it with anyone who might be interested. If you think there’s something that could be amended or added, please do get in touch (heythere@wemadethis.co.uk) – I’ll update the information periodically.